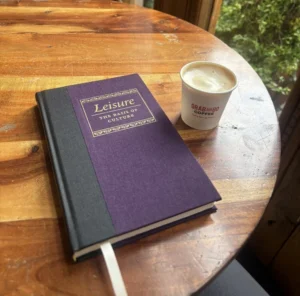

These past Christmas days allowed me to read one of the best books I have ever read, and very likely one of those that will accompany me throughout my entire life: Leisure: The Basis of Culture by Josef Pieper. For some time now, I had been thinking about the noise of our internet-driven world. The …

These past Christmas days allowed me to read one of the best books I have ever read, and very likely one of those that will accompany me throughout my entire life: Leisure: The Basis of Culture by Josef Pieper. For some time now, I had been thinking about the noise of our internet-driven world. The algorithm knows us better than we know ourselves, and thus serves us precisely the things that satisfy us momentarily and pleasingly. Yet after many hours in front of screens, at the end of the day, the soul feels emptier than ever, guilty for not having achieved as much as it would have liked to have achieved that day. So where did leisure go? Where did rest go? The very purpose of resting and relaxing was precisely the impulse that led us to spend time in front of a few “memes” and other posts that, presumably, relax the human mind. Instead of leisure, the human person, without even realizing it, has added useless work to himself, burdening both soul and body. And there is no heavier work than useless work.

What is leisure?

According to Josef Pieper,

Leisure is a form of silence—that kind of silence which is a prerequisite for understanding reality: only the silent can hear, and those who do not remain silent do not hear. Silence, as used here, does not mean a “closed mouth” or a mere “absence of noise”; rather, its closest meaning is that the soul’s capacity to respond to the reality of the world remains undisturbed. For leisure is a receptive attitude of the mind, a contemplative stance … and the capacity to place oneself within the whole of creation.1

To be at leisure does not mean being unemployed or lazy. Leisure does not simply imply the absence of work, but rather a mental and spiritual state of calmness that allows things to flow naturally. Pieper compares such a person to someone who falls asleep. In order to sleep, a person does not need to carry out something actively. He simply needs to come to peace and let things flow on their own. Precisely being active prevents sleep, and being active while not allowing the mind any leisure prevents our soul from intellectually and really grasping the whole of the world in which it lives, because “the human soul is sometimes visited by an awareness of that which holds the world together precisely in these quiet and receptive moments.” 2

Leisure, therefore, is not the absence of our daily tasks or duties, even though almost all of us perceive leisure in this way. Leisure is, better said, the freedom of time. It is a time in which one finds freedom. Consequently, for someone to find freedom, he must first know what freedom is. This short piece is not the place to treat the concept of freedom at length, but a comparison that Aristotle makes between metaphysics and the free man will suffice for us. He says: “Just as a free man exists for himself and not for another, so too this science (metaphysics) is the only one among the sciences that is free.”3 A free man, therefore, exists for himself and is not the slave of someone else. In the same way, leisure exists for itself and is not in the service of something else. By this, of course, I mean that it is not actively in the service of something else. Passively, since leisure allows the mind to remain open to the reality of the whole of creation, it becomes, ironically, more productive for the human being than his most sweat-inducing activity.

But what does truly happen in our world? It is noisy, resounding from all sides. Our world is built for people who do not rest—indeed, who are not meant to rest. We have become like those poor mobile phones that are kept on charge while being used, which, although they need rest in order to recharge, are abused by being used until they overheat so much that they freeze. Such robotic activity is characteristic of a consumerist world that does not wish to make room for contemplation. The belief that the one who works a great deal and works hard does well is typical of our time, but entirely contrary to the thought of Saint Thomas Aquinas: “The essence of virtue consists in the good, and not in the difficult.”4 Something difficult is not necessarily good. Nevertheless, people today are encouraged to work so hard that when they rest, they feel unproductive or even lazy. Even the rest they take is only in the service of work, to recharge their energy so that they may work the next day. It should not be this way. Man ought to work in the service of rest.

Our very nature confirms such a thing. While we are at work, we eagerly await the arrival of leisure time and holidays. The money we earn, we wish to turn into gifts and food and drink for celebrations. This connection between leisure and celebration, Pieper explains very well, and he even takes it to an even deeper level:

The spirit of leisure, it can be said, lies in “celebration.” … But if “celebration” is the essence of leisure, then leisure can be made possible and truly justified only on the same basis as the celebration of a feast, and that formation is divine worship.5

Pieper explains how divine worship is for time what the temple is for space. The temple is a space set apart for the gods, a land in which one neither lives nor cultivates. In the same way, divine worship is a time set apart, which likewise is not used for ordinary things, but specifically for its appointed purpose.

I do not want to go too deeply into the issue of the Sabbath, but I want to connect it somewhat with our reality. The Word of God says: “Remember the Sabbath and keep it holy”.6 According to apostolic tradition, the Church has set apart Sunday for divine worship, because it is precisely the day when Christ rose, the “first” day of the week that commemorates the day of creation, and at the same time the “eighth” day that inaugurates the new creation. The Catholic Church teaches that

On Sundays and other holy days of obligation, the faithful are bound . . . to abstain from those labors and business concerns which impede the worship to be rendered to God, the joy which is proper to the Lord’s Day, or the proper relaxation of mind and body.7

Rest from the ordinary tasks of daily life is not simply a command. It arises from the natural law, and therefore, it is something necessary for human nature. He who does not rest cannot work. He who does not rest cannot think. He who does not rest cannot worship. He, then, who does not rest, is not a complete human being.

It was impossible for me not to include the rest of the Lord’s Day in this writing, and equally impossible for me not to see the connection between the lack of rest and the lack of divine worship. We live in a highly confusing time. On the one hand, we have more time and resources to advance in life far beyond all our predecessors in history. On the other hand, we are deeply submerged in the everyday, highly stressed, and mentally exhausted. I think this mental and spiritual fatigue, which also leads to physical exhaustion, is an unavoidable consequence of the absence of true rest in leisure time.

Our leisure is by no means free. It has been enslaved by empty habits, by excessive scrolling through “reels” and “shorts,” which have reduced our time for concentration. According to studies, the average attention span in 2004 was two and a half minutes, whereas in 2012 it was only 75 seconds.8 I will leave to you the imaginary calculation for the year 2026, when even the algorithms of “reels” and “shorts” will recommend that we keep videos under 30 seconds so that they are fully watched. It would not be surprising if many people who started this article have not reached this paragraph. This shows that our brains are adapting to a world for which they were not created.

We were made to contemplate, not to act robotically. We were not programmed to carry out things habitually, without thought, desire, or impulse. We were created in the image of God, and if God Himself rested after creation, then we, too, must rest. If God rested to contemplate His creation, His love for it, and His glory, how much more do we need to rest, we who do not know as the Almighty knows, do not have power over our lives as the Omnipotent, and do not have the inexhaustible strength of Him who is eternally Blessed. We need to pause the flow of our lives for a moment, to think deeply about the things that truly matter: our soul, our holiness, the love we have for God and for the people in our lives. But in order to think about these things, we must first reflect on their source. Certainly, the Christian is clearer about this, since it has been revealed to him that “every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights”9, but even one who is not a Christian must pause and philosophize about these fundamental things in life. Neither Plato nor Aristotle knew this biblical verse, yet in their own way, they reflected on truth, on life, on the divine, and on everyday existence.

Far from philosophizing, we have fallen prey to a mechanism that decays the brain, and therefore the soul. We go to work bored, carry out our tasks with complaints, and come home exhausted; we spend a few hours on the phone and go to sleep. Even when we eat, we cannot remain without screens. This happens because we do not take a moment to think. Our soul and mind are shrinking day by day. We do not have the capacity to reflect on the fundamental truths of life; indeed, we mock those who try to speak to us “about faith” or about philosophy. I understand that not everyone is in a position to grasp that divine worship is the essence of life, but we are all capable of understanding that each of us must set aside specific moments to close the doors to the world, turn off the screens, shut our senses to the everyday world, and open our eyes and ears to the voice of silence, of calm, and of the divine order that reigns in creation. This kind of rest is owed to our mind and body. To sit in silence, to think, to breathe without worrying about the tasks we must carry out tomorrow—and we will discover that life is deeper, that our concerns do not deserve such clamor, and that our soul and body were created for something higher.

It is no surprise that a world that does not rest does not worship. Nor is it surprising that a world that does not rest fails to understand where it comes from and where it is going. It is, therefore, no surprise that our world is content to follow the flow of daily life robotically and does not reflect on the basic truths of life: What is man? Where did he come from? What is his ultimate purpose? What is moral? What is ethical? By what impulse should we wake in the morning? Why must we work? All of these questions, which seem monstrous, are at the heart of our everyday life, but they receive answers only in truly free time. Dispersed leisure is worse than work, because work at least has direction and outcome, but one who is distracted during leisure wastes both the time and the freedom that could have been discovered in that time.

What encouragement can we find? The words of Pope Benedict XVI, preached on August 21, 2011, during an audience with hundreds of thousands of young people in Madrid, give us hope and speak to our hearts to move forward with faith and courage:

You will be swimming against the tide in a society with a relativistic culture which wishes neither to seek nor hold on to the truth,” he added. “But it was for this moment in history, with its great challenges and opportunities, that the Lord sent you, so that, through your faith, the Good News of Jesus might continue to resound throughout the earth.10

Through the cultivation of spiritual values by the wise use of leisure, we can stand up to a relativistic world that neither wishes to philosophize itself nor wants to allow others to reflect on the basic things of life. Resources are (overly) inexhaustible. Work and money are more abundant than ever. Knowledge knows no limit. Everyone has immediate access to the information they need. Yet only the one who lives wisely, the one who truly reflects on the truths of life, the one who esteems leisure as he esteems life itself, will know how to seek truth and holiness, and will surely find them and be blessed in his days.

Join the Club

Like this story? You’ll love our monthly newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing to the newsletter.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please try again later.