Introduction The proposed research aims to explore the concept of "fragmented knowledge", which is that the notion that knowledge, as it is received, interpreted, and reconstructed over time, is inherently fragmented and distorted. This fragmentation often results in various epistemological fallacies that can affect the development and understanding of new concepts. This study seeks to …

Introduction

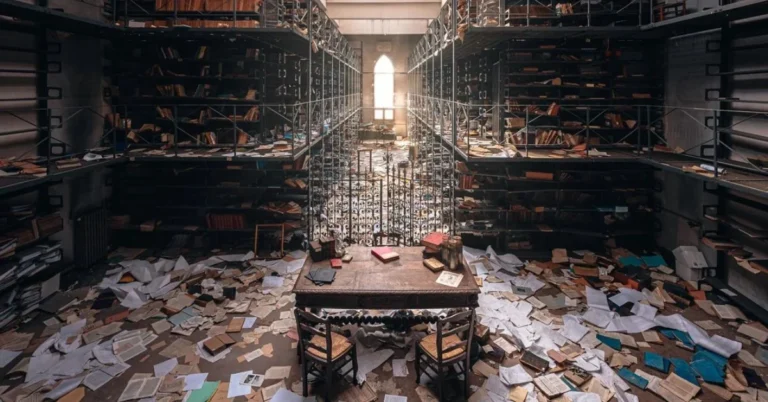

The proposed research aims to explore the concept of “fragmented knowledge”, which is that the notion that knowledge, as it is received, interpreted, and reconstructed over time, is inherently fragmented and distorted. This fragmentation often results in various epistemological fallacies that can affect the development and understanding of new concepts. This study seeks to elucidate how these fragmented pieces of knowledge influence philosophical thought and the broader epistemological landscape, particularly considering the heterogeneity inherent in the notion of knowledge itself (Cléro, 1970). I further investigate how these fragments, exacerbated by cognitive vulnerabilities and the need for heuristics, contribute to epistemological challenges, especially in an era where digital dissemination accelerates knowledge exchange (Nguyen, 2023). This perspective aligns with a “hostile epistemology” framework, which scrutinizes how environmental factors exploit inherent cognitive limitations and vulnerabilities in knowledge acquisition and processing, particularly given the overwhelming volume of information we constantly encounter (Nguyen, 2023).

This necessitates a deeper understanding of how epistemic processes are compromised, leading to an ignorance crisis despite advanced methods of knowledge acquisition and communication (Simion, 2024). This essay also addresses how disinformation and knowledge resistance, coupled with an over-reliance on readily accessible information, contribute to the propagation of false beliefs and hinder the development of accurate conceptual frameworks (Simion, 2024).

Through this examination , i will critically assess the role of contemporary information environments, such as social media and AI-driven knowledge delivery systems, in both facilitating and exacerbating knowledge fragmentation and the subsequent emergence of epistemic fallacies (Anderau, 2023; Clark et al., 2025).

Fragmented Knowledge as an Epistemological Concept

The notion of fragmented knowledge refers to epistemic states in which agents possess partial, decontextualised, temporally disjoint, or insufficiently integrated information within coherent conceptual frameworks. Fragmentation does not merely denote ignorance or lack of information; instead, it describes a condition in which agents hold some epistemically relevant content yet lack the structural unity required for reliable understanding or justified belief. This structural disintegration can impede the development of comprehensive experience and the formation of collective knowledge, particularly within complex epistemic networks (Milano & Prunkl, 2024).

I believe that this distinction is pivotal. Whereas ignorance constitutes the mere absence of knowledge, fragmented knowledge represents its flawed or imperfect possession. Likewise, uncertainty pertains to varying levels of confidence, whereas fragmentation relates to the organization and integration of epistemic material. An epistemic agent might exhibit both confidence and informational awareness, yet remain epistemically deficient if their inputs are disaggregated and inadequately synthesised. This condition frequently manifests as “informed ignorance,” wherein individuals amass copious data points without the capacity to forge a unified, precise understanding, thereby exacerbating the global ignorance crisis (Cohen & Garasic, 2024; Simion, 2024).

The heterogeneity of knowledge, as emphasized by Cléro (1970), further complicates this picture. Knowledge is not a monolithic entity but comprises diverse forms: propositional, procedural, testimonial, and practical,each governed by different epistemic norms. Fragmentation arises when these heterogeneous elements fail to cohere, yielding epistemic states that appear robust locally yet collapse under broader scrutiny. This structural incoherence is amplified by digital platforms, which often prioritize engagement over epistemic coherence, leading to further epistemic fragmentation through algorithmic filtering and the formation of ‘filter bubbles’ (Mattioni, 2024).

Fragmented knowledge can therefore be understood as a hybrid phenomenon: it arises partly from cognitive limitations intrinsic to epistemic agents, and partly from external informational structures that shape how knowledge is acquired, transmitted, and retained. Establishing this dual character provides the conceptual foundation for analysing both the mechanisms and consequences of fragmentation. I will further work to delineate these mechanisms, explore their role in fostering epistemological fallacies, and propose strategies for mitigating their pervasive impact on philosophical and, even more importantly, epistemological discourse.

Mechanisms of Knowledge Fragmentation

A convergence of cognitive and structural mechanisms drives knowledge fragmentation. At the mental level, agents operate under conditions of bounded rationality: limited attention, finite memory, and constrained processing capacity. These limitations necessitate reliance on heuristics, cognitive shortcuts that enable efficient decision-making but often at the cost of epistemic precision. Such reliance can lead to oversimplification, selective attention to information, and the decontextualization of complex concepts, fostering “informed ignorance” where individuals possess information but lack an accurate understanding (Cohen & Garasic, 2024).

Heuristics promote fragmentation by privileging salience over relevance and accessibility over coherence. Information that is emotionally charged, recently encountered, or socially reinforced tends to dominate belief formation, even when it lacks contextual grounding. Over time, this produces epistemic assemblages composed of disconnected informational fragments rather than integrated bodies of knowledge. Furthermore, the digital transformation of knowledge order, characterized by flexible phases and flattened hierarchies, exacerbates fragmentation by destabilizing traditional epistemic practices and enabling the rapid dissemination of epistemically toxic content (Mattioni, 2024; Neuberger et al., 2023).

Temporal factors further exacerbate fragmentation. Knowledge is rarely acquired continuously or systematically; instead, it is accumulated across disparate contexts and moments. Without deliberate epistemic integration, earlier informational fragments may persist unchallenged, coexisting with newer inputs in ways that generate inconsistency or false coherence. This temporal discontinuity is particularly problematic in domains where information evolves rapidly, leading to outdated or conflicting understandings that resist revision. Moreover, the erosion of human connections and the rise of micro-identities in digital spaces further accelerate this fragmentation, creating parallel social realities that lack cohesion with broader societal understanding (Kossowska et al., 2023). This phenomenon contributes to an overall epistemic crisis in which traditional knowledge orders are destabilized, leading to widespread false beliefs and distrust in expertise (Neuberger et al., 2023; Simion, 2024).

Structural mechanisms also play a decisive role. Modern epistemic agents are deeply dependent on testimony, mediated sources, and institutional knowledge systems. This epistemic dependence increases vulnerability to fragmentation, as agents often lack the means to verify or contextualise the information they receive independently. Fragmentation thus emerges not merely from cognitive weakness, but from the architecture of contemporary knowledge transmission itself. This reliance on external sources, particularly in rapidly polarizing digital environments, can lead to epistemic fragmentation, where conflicting narratives replace shared understanding and objectivity in reasoning collapses (Lee et al., 2025).

Epistemological Fallacies Arising from Fragmentation

Fragmented knowledge systematically gives rise to distinct epistemological fallacies. One prominent example is false coherence: the tendency to impose an illusory unity on disparate informational fragments. Agents may infer overarching explanations or patterns where none are epistemically warranted, mistaking narrative plausibility for justification. This fallacy is particularly pernicious in public discourse, where simplified narratives often gain traction despite lacking empirical support or logical consistency. This can lead to significant societal epistemic fragmentation, where a lack of trust in common epistemic authorities proliferates disagreement over factual beliefs (Abiri & Buchheim, 2022). This condition is far more perilous than the dissemination of mere misinformation, as it corrodes the foundational trust necessary for collective knowledge production and societal cohesion (Abiri & Buchheim, 2022).

Another recurrent fallacy is overgeneralisation from partial information. Fragmented knowledge often involves extrapolating broad conclusions from narrow evidential bases, particularly when fragments are emotionally salient or socially reinforced. This undermines both justificatory standards and reliability conditions for knowledge. Such inductive leaps, unsupported by comprehensive data, lead to an exaggerated sense of understanding, contributing to a crisis where individuals struggle to discern reliable information from unreliable sources, especially in an environment saturated with politically motivated reasoning and disinformation (Simion, 2024; Stones & Pearce, 2021). Furthermore, the proliferation of generative AI systems exacerbates this by creating recursive knowledge loops that lack robust empirical anchoring, further destabilizing epistemic infrastructures (Singh, 2025).

Fragmentation also contributes to epistemic overconfidence. Possessing multiple fragments can create the subjective impression of comprehensive understanding, even when critical gaps remain unrecognised. This form of overconfidence is especially resistant to correction, as agents interpret challenges as threats to coherence rather than opportunities for epistemic revision. This cognitive bias is often reinforced by epistemic vices such as rigidity and indifference, which hinder critical self-assessment and the integration of contradictory evidence (Meyer, 2023).

At the collective level, fragmented knowledge produces group-level epistemic failures, including polarisation and echo-chamber effects. When fragments circulate within homogenous communities, they acquire artificial stability, reinforcing shared misconceptions and insulating them from external critique. Fragmentation thus undermines not only individual epistemic agency but also the social mechanisms upon which knowledge depends. The advent of generative AI further complicates this landscape by creating new pathways for amplified and manipulative testimonial injustice, alongside hermeneutical ignorance and access injustice, thereby undermining collective knowledge integrity and democratic discourse (Kay et al., 2024).

Hostile Epistemology and Environmental Exploitation

The framework of hostile epistemology offers a powerful lens for understanding why knowledge fragmentation persists and intensifies. Hostile epistemic environments are structured to exploit cognitive vulnerabilities rather than to mitigate them. They prioritise engagement, speed, and affective response over accuracy, coherence, and epistemic responsibility (Nguyen, 2023).

In such environments, fragmentation is not accidental but incentivised. Algorithms reward content that captures attention quickly, regardless of its epistemic quality. This encourages the dissemination of isolated fragments stripped of contextual scaffolding, as such fragments are more likely to provoke immediate reactions.

Hostile epistemology shifts explanatory focus away from individual epistemic failure and toward systemic design. Epistemic agents are placed in environments that systematically undermine their capacity for responsible belief formation. Fragmentation, on this view, is an expected outcome of rational agents operating under adversarial informational conditions.

This perspective also illuminates the moral dimension of epistemic harm. When environments are structured to exploit cognitive weaknesses, responsibility for epistemic failure becomes distributed across agents, institutions, and technological systems. Fragmented knowledge thus emerges as a structural injustice rather than merely a personal shortcoming.

The Ignorance Crisis and Knowledge Resistance

The persistence of fragmented knowledge contributes to what has been described as an ignorance crisis: a condition in which increasing access to information coincides with declining epistemic reliability (Simion, 2024). Fragmentation plays a central role in this paradox by generating epistemic states that resist correction.

Disinformation thrives in fragmented epistemic environments by exploiting existing informational gaps and cognitive biases. Once integrated into an agent’s fragmented belief set, false information becomes difficult to dislodge, particularly when it aligns with prior commitments or identity-defining narratives. This resistance is often compounded by socially supported ignorance, where communities reinforce and validate beliefs that conflict with expert consensus, leading to entrenched “bad beliefs” that are epistemically irrational yet socially normative (Müller, 2024; Woomer, 2017).

Knowledge resistance further entrenches fragmentation. Agents confronted with corrective evidence may reject it, not because of lack of access, but because it threatens their perceived coherence. Fragmented knowledge thus becomes self-stabilising: attempts at correction are interpreted as attacks rather than epistemic improvements. This phenomenon is particularly salient in the digital age, where epistemic fragmentation is exacerbated by societal divisions and a lack of trust in common epistemic authorities, rendering traditional fact-checking less effective (Abiri & Buchheim, 2022).

This dynamic undermines traditional epistemological assumptions about rational revision and convergence on truth. In fragmented environments, epistemic disagreement does not resolve through shared evidence, but instead hardens into mutually insulated belief systems. Consequently, the very notion of a universally accessible and coherent body of knowledge is challenged, leading to a profound re-evaluation of epistemic foundationalism in an era of information overload and partisan divides (Strömbäck et al., 2022). Therefore, this research aims to provide a robust framework for comprehending these dynamics, fostering a more nuanced understanding of how knowledge is constructed and deconstructed in complex socio-technical systems.

Digital and AI-Mediated Knowledge Environments

Contemporary digital environments significantly amplify epistemic fragmentation. Social media platforms fragment knowledge through brevity, context collapse, and algorithmic curation. Information is presented as isolated units optimised for consumption rather than understanding, encouraging shallow engagement and rapid belief formation. Furthermore, generative AI exacerbates this by creating recursive knowledge loops that lack robust empirical anchoring, further destabilizing epistemic infrastructures (Kay et al., 2024).

AI-driven knowledge systems introduce additional complexities. While such systems can enhance access and efficiency, they often operate in an opaque manner, obscuring the sources, limitations, and confidence levels of the information they provide. Automated summarisation and content generation risk further decontextualisation, producing outputs that appear authoritative yet lack epistemic transparency. This inherent opacity can foster an unwarranted trust in AI-generated content, potentially exacerbating the spread of fragmented or even disinformative knowledge (Simion, 2024).

Speed and scale are decisive factors. The accelerated circulation of information leaves little opportunity for reflection or integration, reinforcing heuristic processing and fragment retention. AI systems may therefore mitigate certain epistemic burdens while simultaneously intensifying fragmentation if deployed without epistemic safeguards. The challenge, thus, lies in developing AI systems that not only provide information but also facilitate a deeper understanding of their epistemic provenance and limitations, fostering a more robust and integrated knowledge ecosystem (Clark et al., 2025).

The epistemic challenge posed by these systems is not merely technological but normative: determining how knowledge ought to be structured, delivered, and evaluated in environments that prioritise efficiency over understanding. This is especially critical given that generative AI can fragment societies into separate epistemic communities, thereby eroding the common factual ground necessary for democratic discourse and collective action (Abiri & Buchheim, 2022).

Mitigation Strategies and Epistemic Repair

Addressing fragmented knowledge requires both individual and structural interventions. At the individual level, epistemic virtues such as humility, intellectual patience, and sensitivity to evidential gaps can mitigate fragmentation. Practices that slow cognition and encourage integration—such as reflective deliberation and source triangulation offer partial resistance. However, these individual-level strategies are often insufficient in the face of systemically hostile epistemic environments (Coeckelbergh, 2025).

However, individual strategies are insufficient in hostile epistemic environments. Structural interventions are therefore necessary. These include designing platforms that introduce epistemic friction, promote contextualisation, and foreground uncertainty rather than suppress it. Institutional safeguards, such as epistemic auditing and transparency standards for AI systems, are also essential. Such measures would help counteract the propensity of advanced AI to exacerbate cognitive overload and propagate biases that undermine diverse global knowledge systems (Ofosu-Asare, 2024; Salem, 2025).

Crucially, mitigation strategies must avoid epistemic idealisation. Fragmentation cannot be eliminated; it can only be managed. Epistemic repair is necessarily partial and fragile, constrained by the very cognitive and environmental factors that generate fragmentation in the first place. Therefore, a robust framework for understanding and addressing fragmented knowledge must acknowledge its pervasive nature while focusing on strategies that enhance epistemic resilience and foster more integrated forms of understanding (Wihbey, 2024).

Conclusion

We conclude that Fragmented knowledge is not an abnormal deviation from ideal epistemic conditions but a structural aspect of modern epistemic life. It results from the interaction of cognitive limitations, diverse knowledge types, and hostile informational environments. Its effects—epistemic fallacies, ongoing ignorance, and resistance to correction—present significant challenges to traditional epistemological frameworks. The spread of artificial intelligence further complicates this landscape, as AI systems can both worsen fragmentation through biased information sharing and provide potential opportunities for more robust knowledge integration, depending on their design and ethical use (Coeckelbergh, 2025; Ofosu-Asare, 2024).

Recognising fragmentation as a systemic phenomenon necessitates a shift toward non-ideal epistemology, one attentive to real-world constraints and adversarial conditions. Only by acknowledging these constraints can epistemology remain responsive to the epistemic crises of the digital age. This understanding informs the subsequent exploration of specific mechanisms underpinning fragmentation and their manifestation in historical and contemporary philosophical discourse. The following sections will therefore delve into the precise mechanisms by which knowledge can become fragmented over time and how these processes contribute to the formation of epistemological fallacies, ultimately proposing strategies for enhancing knowledge synthesis (Pillin, 2025). This includes exploring the role of epistemic responsibility in hybrid human-AI knowledge systems, recognizing that defragmentation, while epistemically rational, often necessitates practical considerations for its successful implementation (Pillin, 2025). Furthermore, such an approach requires a nuanced understanding of how individuals integrate disparate pieces of information and how AI-mediated processes can either hinder or facilitate this integration (Clark et al., 2025; Rich, 2023).

Join the Club

Like this story? You’ll love our monthly newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing to the newsletter.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please try again later.